BY MIKE METTLER – MAY 12, 2017

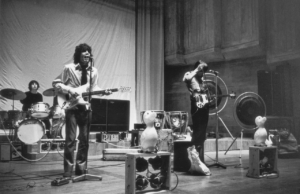

Three-quarters of Pink Floyd in the frame, putting on the quad show at Games for May at QEH in London on May 12, 1967. Roger Waters is at right, hand on head.

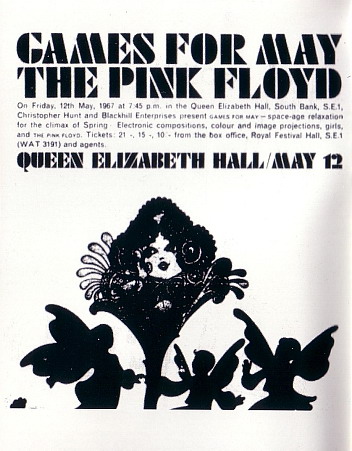

50 years ago today, Pink Floyd headlined Games for May on May 12, 1967, at the Queen Elizabeth Hall (QEH) in London. The show was billed as “Space age relaxation for the climax of spring – electronic composition, colour and image projection, girls, and The Pink Floyd.” (The word “The” was still part of the band’s name at the time, BTW.)

Besides the presentation of an innovative light show, Games for May also featured one of the earliest examples of live quad/live surround sound, with keyboardist Rick Wright manipulating mostly pre-recorded sounds around the room via the device known as the Azimuth Coordinator. (See-eee-eee Emily Play, indeed…)

In recent years, I’ve had the opportunity to speak with two Pink Floyd bandmembers – bassist/vocalist Roger Waters and drummer Nick Mason – about Games for May, and its ensuing/ongoing impact. First up, here’s the word-for-word in-person exchange I had with Waters about it in New York on September 15, 2015.

Mike Mettler: Let me pick a date out of the air – May 12, 1967, which as far as I can tell, was the first live quadrophonic performance by a rock act, anywhere.

Roger Waters: Mm-hmm. Games for May.

Mettler: How did that decision come about? Nobody had done that before, so what was your thought process as an artist for doing it?

The infamous Azimuth Coordinator in question.

Waters: That’s a very interesting question. I think probably it had something to do with Bernard Speight at EMI, because we had asked him to design a pan pot, the Azimuth Coordinator. He built a mono one – well, not a mono pot, obviously, it had one in and four outs. Yeah, so they were two big, old-fashioned 270-degree pots converted to 90, as I recall, with the gimbal [i.e., the control] in the middle, so it was like the universal drum – well, you probably know all about it. But I have no memory of why we tried to use that in the room.

Mettler: And that discussion took place at Abbey Road, because he [Speight] was an engineer there.

Waters: He was, yeah. He was a maintenance engineer at Abbey Road. But I do know that I must have had one of the prototypes or early ones at home, because I made (slight pause) – it can’t be ’67; it doesn’t seem possible that we made any quadrophonic tapes, because there was no 4-tracks then.

Mettler: Nick said you had mono tapes that you and he both put together that could be manipulated around the room.

Waters: Yeah, I think that’s probably true. I remember making the tapes. I was working in a very cold basement off Harrow Road in London, on my own. What I was doing was taking – I made bird-song tapes, but I made them vocally. So I’d make vocal noises and then speed them up until they sounded like birdsong. Just whistling and chirping and stuff like that.

But I also remember making tapes that were nothing but edge tones of cymbals, with beaters. You’d get a cymbal going like that [mimes hitting a cymbal], get a microphone, and bring it up to the edge of a cymbal until you got that [makes noise] “hmmmmm-wrowwwwwww-wrowwwwww” – noise that you get off the edge of a cymbal if you put your ear up against it. (chuckles) So I remember doing that.

Other things – I do remember, during the show (chuckles), I had cars about that big [hands close together, leans over table to mime it] with flywheels, these cars that you go [mimics moving hand across wheels to rev them up], and I would go like that, get one going, and put it on the floor of the stage, and run after it with a microphone. (both laugh) And that would go into the PA, or somebody else would put it into the quad, and you’d get this weird “krrrrrrrrrsssshhhh” noise coming out.

Pink Floyd’s Rick Wright at the keys, Syd Barrett at the mike, and Nick Mason on the kit, at Games for May at QEH on May 12, 1967.

We did a lot of weird things in that show. We did a thing probably aping Barry Humphries, who, in his [Dame] Edna Everage persona, would throw gladioli into the audience. We did a big thing. We threw tons and tons of flowers into the audience – they were all over, everywhere. They never let another pop group in that hall [Queen Elizabeth Hall, a.k.a. QEH] again. We’d made too much of a mess. (chuckles) Yeah, we made a terrible mess with flowers.

But it’s funny that the title of the concert, was Games for May, which obviously is a lyric from one of our songs –

Mettler: “See Emily Play” – The line is, “Free Games for May,” or something like that…

Waters: Yeah. (Sings), “See-eee-eee Emily play…” Yeah, and that was Blackhill [Enterprises, their management company], so that was Andrew King and Peter Jenner, and the guy who was the promoter of the concert was called Christopher something, I can’t recall… [It was Christopher Hunt, a classical promoter.] I don’t know if we ever worked with him again. (chuckles) But it was fun.

Mettler: As a sound creator, do you recall the impetus for that – “Rather than just stereo or mono, I’d really like to hear things throughout the entire space”?

Waters: Yeah! Well, it’s such a long time ago; I can’t remember the nuts and bolts. Even if I could [adopts posh tone]: “Oh, I remember I was sitting in my chair, you know, in my bedroom above Blackhill Enterprises, where I lived for a time. And I remember having this idea and writing it down and going, ‘Oh! I’ve just invented quadraphonic sound!’” (MM laughs)

Mettler: Why do you like live quad and live surround sound? Why is it interesting to you?

Waters: Ohhhhh… (pause) The very simplest things are just very cool. That’s why we started using the system – people started working in quadrophonic mode, but they always had front left, front right, back left, back right. And almost certainly this was my idea (laughs), but it’s quite clear that’s not the way the brain works. The brain goes front, back, right, left. It doesn’t go front left, front right – I mean, it did for a bit with stereo, only because it was like that and you could move something across the wall like that. But really, the brain is more interested in that, so that’s the way we used it. That’s what we did, and what we did through all the shows. And that’s what I did in The Wall, as well. That’s the system in The Wall.

And now, it’s Nick Mason’s turn to chime in, from a discussion he and I had in New York on June 20, 2011.

Mike Mettler: From what I can gather, May 12, 1967, at Games for May, was the first date of an actual live quad performance with the Azimuth Coordinator.

Mike Mettler: From what I can gather, May 12, 1967, at Games for May, was the first date of an actual live quad performance with the Azimuth Coordinator.

Nick Mason: To be accurate, that’s correct. That was Games for May, at Queen Elizabeth Hall, and it was a quad performance, but it was not a quad recording.

Mettler: Right. I’m curious how it was decided. Who said, “We’re going to be play live in quad”? How did the decision come about? Who thought of that?

Mason: I think it was a conversation at Abbey Road [Studios] with a couple of the engineering staff there. There was a guy called Bernie Speight, who went, “Oh yeah, I can build one of those,” and then he built the original quad box [i.e., the Azimuth Coordinator]. It had two controls. So when we went to the Queen Elizabeth Hall, what actually happened was if there was something on tape, it was on mono tape; it wasn’t stereo. And then it was panned around to the speakers for the quad effect. It wasn’t a quad tape.

So I think the mixing desk had access to one part — they were doing the footsteps and things like that, and those were from tapes that Roger and I had devised. And the other one was for Rick, who used it for storms and drones and other sounds.

Mettler: So when this idea came about, your response as a performer was. . . what? You’d not necessarily heard live music like that before. What did you think of the idea?

Nick Mason conducts some of the proceedings at Games for May at QEH in London on May 12, 1967.

Mason: What happened was — the show was quite, I’m trying to think of the word, it was quite “arty.” This was not a matter of talking about how to present a show called “Rock Something,” if you like. There were a lot of sound effects and things going on onstage. There were long pieces that might have an organ wafting away. There’d be a lot of “dripping” sounds, all these sound effects going.

Mettler: Perhaps influenced by the fact that you had access to the sound library at Abbey Road?

Mason: Yes. I think Michael Perry got the nature of what we were thinking about actually doing, so there was this journey through a labyrinth with me, so there’d be the wind noises and the sounds of dripping. Because I remember one of the things we had, one of the jokes, was this guy dressed as a gas-masked monster, and I think a number of people were probably freaking out over that, in a chemically enhanced state.

So when we were planning that, I think we were looking for anything that would make the show more entertaining and more interesting. At the time, the audience perhaps expected more than a rock & roll show. So we were trying to direct it toward something a little bit more theatrical.

Mettler: So it really started more as using effects, instead of sending the music all around you. As a performer and creator of this music, did you start thinking, “Hey, we could actually create music in 360 degrees”?

Mason: Well, that’s the thing about technology — as creators, you sometimes go for things before it actually arrives. I’m thinking of quad now, not when we finally had all of the speakers needed for surround. Then it would be fine, you could then afford to pre-mix each individual element.