BY MIKE METTLER — APRIL 18, 2014

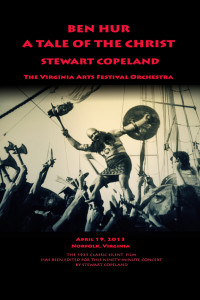

Never let it be said that Stewart Copeland has idle hands. The innovative Police percussionist and ace composer has been working tirelessly on composing a soundtrack to MGM’s 1925 silent film Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, which, in addition to being a legendary broad-sweeping and groundbreaking epic tale, is on record as being the most expensive film made in the silent era. Copeland’s score receives its world premiere Easter weekend on April 19 at the Virginia Arts Festival in Norfolk, Virginia, where it will accompany his 90-minute edit of the movie.

Recently, Copeland, 61, and I discussed how restoring Ben-Hur was both invigorating and taxing, his philosophy about surround-sound scoring, some of the secrets behind his infamous snare drum sound, and a few Police-related matters.

Mike Mettler: I’m extremely fascinated about your Ben-Hur restoration.

Stewart Copeland: Well, it is a humdinger. It all began with an arena tour [in 2009] where they staged Ben-Hur live in the arenas with a full-on chariot race and pirate battle; the whole schmear.

Mettler: Why did you decide to tackle this as a project?

Copeland: It was an incoming call way back when the arena show went up. I wasn’t a particular fan of Ben-Hur — yet. But as I got into it with the book, the show, and the two movies — the Charlton Heston one [1959], and the 1925 one, the one I worked on — I got deep into it.

Mettler: I was looking at some of the 1925 footage you posted online, and it’s astounding what was done back then. I kept thinking, “This was shot in 1925?”

Copeland: They had to do it all in front of the camera! It was the biggest movies of the silent era. It cost 4 million [said with Dr. Evil inflection] dollars. Getting the print out of deep freeze was an adventure too. It took a week to defrost this 80-year-old piece of celluloid, and the last time it was seen was in the ’60s, when they burned a video from which the DVD that’s out there was derived. That’s what I originally cut up to make my version of the movie, because the music I wrote had to match with the movie I recut. After years of pursuing this at Warner Bros. and navigating the labyrinthian divisions of this giant corporation that owns this material, it just took a while to get from one division to the other and work its way through the system to get to the point where I could actually get my hands on the original piece of celluloid. It looks like a hybrid they put together from two or three prints that were out there in the theaters. They got the cleanest footage from each one, and stuck it all together. The movie was made in 1925, they re-released it in the ’30s, and it’s got a checkered history.

The version I’ve got, I had to curate. It’s not actually black and white, it’s kind of gray and white at this point. [both laugh] So I had to get deep into the balance of the blacks and the whites and process every single shot of the movie, as well as cut down a 2½-hour movie down to 90 minutes, which was an adventure. Having done that, every single shot in the movie had to be treated. Different cameras were used, running somewhere between 18 and 22 frames per second, depending on which camera they were using, and who was cranking that day.

It’s really something, but technology aside, what they did in front of the camera was colossal. The burning Roman galleons crashing into each other, the thousands of extras blazing away and falling into the sea — a few people died in that because the ships did actually catch fire. The production value, the scale, and the spectacle is all really something else. You’re dealing with the frame shape and things like that, which are really small compared to the punch of the movie itself.

Mettler: You’re literally turning into your own Criterion Collection division with this project.

Copeland: No one has ever done it quite like this because I’m presenting the film as a concert, which has directed the way I’ve had to do the edit. And there will be those haters out there, those purists who will come after me with pitchforks, and I’ll try to mollify them as such by saying the original is still there in the box set with the Charlton Heston movie. And that’s definitely worth checking out, but the film looks much better now. Going straight back to the original from digital, there’s just a higher resolution. It looks much better than it did when they transferred it to video, which is a terrible medium.

Mettler: Will you record any of the performances for release on DVD or Blu-ray?

Copeland: At some point. I would not be surprised if we did that.

Mettler: Considering you compositional skills, I’d love to hear a full surround-sound mix.

Copeland: Well, the thing is, at some point, it crosses the line where I’m taking [director] Fred Niblo’s masterpiece and carving it up in a way that he may or may not have approved of. And I think I’m on the right side of the line when I’m doing a concert with a big orchestra, and the drums. The film is a part of that, and I’m not making any representation that this is his movie.

But if, for instance, someone were to record the concert to put out a DVD, that would require a whole other examination of the conscience. I have enormous respect for Fred Niblo. I’m very, very respectful while I’m screwing around with what he did. I’m trying to follow his logic.

Mettler: Does surround sound interest you as a film composer?

Copeland: Not so much, actually. I found that when I was working in film, whenever music came out of more than two speakers, it kind of lost its punch. There’s something to do with phasing, and there’s a lot of voodoo connected with how do you get it to sound good in 5.1 or 7.1. I’ve never succeeded. Every time we threw it [a score] to surround sound, it lost its punch. It’s coming out of stereo, or LCR — left, center, right — in front of you, then it kicks.

That’s just an audio thing. It’s counterintuitive. You would think the music would sound great, having it coming from all around you. And indeed it does, if you’re sitting in the middle of the orchestra. But the way speakers work — I just never quite succeeded in keeping the punch while having the surround.

Mettler: I agree that feeling like you’re in the middle of an orchestra, or any performance, is the best use of surround.

Copeland: Yeah, the thing is, it can be done. A buddy of mine in Primus, Les Claypool, really got into it. He played me some surround he did where it really does rock. And that’s Primus: a heavy, hairy rock band.

Mettler: I just talked to Les a few weeks ago, in fact. I think the surround mix he did last year for the Deluxe Edition of [1991’s] Sailing the Seas of Cheese is fantastically immersive.

Copeland: Ok, yes, that one works. He had already made the record, and he’s gone back in and devoted himself entirely to achieve a good result in surround. That’s a mission all unto itself. And as he showed there, it can be done.

Mettler: Looking at it that way, would you be able to do that with some of your own work from the past, like, say, The Rhythmatist [1985]?

Copeland: Years ago, too many years ago, we did surround for a live Police album.

Mettler: Right, the Syncronicity Concert.

Copeland: From back in the day [1984]. At that time, it seemed like it was ok. You be the judge. We did it here in Los Angeles, and I don’t think we had any particular expertise as to how to really use that medium. To be honest and fair, it’s probably kind of hit and miss.

Mettler: From my viewpoint, a studio Police track like “Secret Journey” [from 1981’s Ghost in the Machine] would be an amazing thing to hear in surround, considering all the subtleties and nuances in it.

Copeland: Yeah. Well, there is a world of audiophiles out there. But my kids, they don’t care about quality. Whatever comes out of their laptop speakers is just fine for them. And there’s something important there, and that is: it’s the music, not just the audio. I remember with Sgt. Pepper — I’m showing my age here — I heard it on the radio, and it sounded great. But the first time I got the album home, and somebody had stereophonic sound, you listened to it with the lights out, and holy moly, what a new experience that was!

Mettler: Do you still like the vinyl medium?

Copeland: I like the sound of it, but I’m much more enamored with the sound of valve amplifiers. And that’s not because they’re accurate, or anything like that — there’s a sound, like an aroma. It’s a form of distortion, in fact, but it has associations that are good associations, and that pumping sound out of a valve amplifier is just a beautiful thing. You don’t really think of it until you turn on an old tube radio, and it just pumps in a cool kind of way.

I’m told by the people who know that that groove in the vinyl has higher resolution than 64k digital, and if you say so… Well, as you know, I’ve lived through several technologies of recording. When I first started, 8-track was a big deal. Then it was 16-track, and it was like, “Oh my God, what are we going to do with all these tracks?” Then it was 24, and then they invented slave reels, and it was unlimited. Then the first Mitsubishi rolled into the studio — digital! Unlimited! 48 tracks! Every time you bounced tracks, you didn’t lose anything. And it went on and on and on. From there, they invented computers — which sounds like I’m joking, but no. They invented computers that were available and smaller than a house.

So that’s three generations right there that audio has gone through, and I’m not that sentimental. I love the sound of a valve amplifier, but you cannot persuade me to go back to an old Studer 24-track — no way, no how. There’s an app for that. That love people have for the way drums slap the tape, you know, the sound you get from that, which is overloading the tape — there’s an app for that, and a pretty convincing app. Meanwhile, I’m not getting out the scissors and cutting that 2-inch tape and carrying around those slave reels — no way, no how. I’m ProTools!

Mettler: So no more razor blades for you, Stewart?

Copeland: No more! Never! I say that having lived through the hell of that Paleolithic era of recording. I’m real happy with modern recording techniques. Because that allows me to concentrate of making cool music, and getting to that cool figure that I want. I can cut straight to the chase of making new music without the technology that has interesting colors but slows the process down.

Mettler: The precision of your snare drum sound has always been a hallmark. Is that something you feel you can capture better now with new technology?

Copeland: No, what I can capture now better is what I’m doing with the snare drum and how I play the snare drum: Getting a good take of me banging on the snare drum can be done much more easily than getting a take on tape. In other words, I can hit that snare drum better with modern technology. Maybe the sound that gets recorded we can argue about whether it’s as good or not. I think it’s pretty good.

Mettler: Dou you still have the same snare from back in the day?

Copeland: Yes, I’ve still got the snare drum I used for all of those recordings right here in my studio, right in my drum set. I’ve got a really romantic name for it: Snare. Sing songs about… [pauses] The Snare. It is a really great drum. It’s kind of a fluke. I’ve had it cloned. My drum company, Tama, has rebuilt that snare drum — the metallurgy, the amount of brass, everything — so I’ve actually got five of them now. But the one on my drum set is the one.

Mettler: Where did you find it?

Copeland: I don’t even know how it got into my collection. Just one day, it was my snare drum, and neither I nor my tech can remember where it first appeared.

Mettler: What makes that snare so special?

Copeland: The thing about it was, I just tuned it really high. It was in an era where the old wave was just going out and the producers would talk about getting a “fatback.” And I’d say, “Fatback? Uhh, what am I gonna do with a fatback?” I remember recording my first album in the ’70s, and the record company threw it out and went and got some new producers to record it “right.” Well, they kicked me out of the studio for a few hours while they got “my” drum sound. They tuned the drums and miked them up. “Ok, they’re sounding great, so now you can play.” And they sounded awful. It was a fatback: [makes thudding noises]. Oh God, dead drums. That was the fashion of the day. So when I had my own band, The Police, I could tune myself. I knew what drums should sound like, and it ain’t that! At the time — it’s not such a big deal now — but at the time, that high-pitched, cracking snare drum was way out of line.

Mettler: What would be the first recorded example where you felt, “Yeah, I totally got it right”? The way it should be?

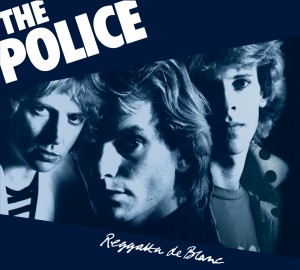

Copeland: I think the second Police album is my favorite-sounding album. That would be Regatta de Blanc [1979].

Mettler: Can’t argue with that. One of my favorite recorded moments of yours is the hi-hat performance on Peter Gabriel’s “Red Rain” [on 1986’s So]. How did that come about?

Copeland: Ah yes. [chuckles] Well, he called up. We knew each other socially, and I was mentioning how I was trying to figure out other ways how to supply the 16th notes in any given song. And the reason we were talking was he already had the same epiphany: “How about I tell the drummer he gets no cymbals?” I was telling him about other things I used like pots and pans, and he said, “Well, come on down and give me some of that!”

So I did! When I went down to his studio there in Bath [Ashcombe Studios], I wasn’t playing on the record, but just on some very weird, vague kind of riffs that he had going. He had Tony Levin in there on bass and a couple other musicians, and we were just kind of screwing around, and later — a long time later — I didn’t recognize any of the songs, because I hadn’t heard any of the songs until the record came out! All I heard was just us doing riffs and grooves, which he cut up and later added lyrics to and wrote songs around, and added chords and actual music. And so, it’s odd. Which tracks did I play on on that album? I’m not even sure! Am I even in there? Peter says so. Ok, I’ll take the credit. I’ve got a platinum album from it, so I guess it was my hi-hat.

Mettler: So is one of the best-sounding recordings from the ’80s.

Copeland: Peter’s a real audiophile. He is really into recording techniques, and just getting it to really sizzle. I’m in too much of a hurry for that, so I’ve been working my entire career with Jeff Seitz for that stuff. It’s a symbiotic relationship. I just breeze on through, but I gotta make it sound good Nowadays. I’m a one-man show in here. Jeff, my engineer, is one of my closest, longest friends, but it’s pretty much social now. Once again, with technology, I’m just in here, and I go straight to it. Click-click-click on the alphanumeric, and I don’t even need any intermediaries anymore.

Mettler: I talked to Andy Summers recently about his new band, the Circa Zero project —

Copeland: It’s pretty good! Ol’ Andy’s raging on the guitar! I love hearing that!

Mettler: He even joked that if The Police ever did another tour, it would probably be a Las Vegas show.

Copeland: Oh, I love the sound of that! Hopefully by such a time, decades from now, Pearl Jam will be playing Vegas, and it’ll be cool. That would be so sweet to roll out of your swank hotel room and go right down to the stage. It’s the fun part of playing without the un-fun part, which is the travel. Going through airports every day — that’s a pain. Playing the same room every night — that’s what we’re here for! That whole Vegas residency thing — all of us super-hip cats who wouldn’t be caught dead playing Vegas are actually full of envy. Oh yeah, book me a flight for Vegas! I’m not sure it’s the right thing for The Police to be doing, but it sounds like a sweet gig.

Mettler: Will The Police be doing anything else?

Copeland: No, I don’t think so.

Mettler: You’ve put the lid on it?

Copeland: Yeah, with the best of intentions. We’re all pretty busy.

Mettler: Well, good luck with Ben-Hur. And to think you owe it all to Francis Ford Coppola. [Coppola asked Copeland to score his 1983 film, Rumble Fish.]

Copeland: Yes! Dear Uncle Francis, this is what you wrought! All your fault. He’s always been very supportive. He saw Oysterhead, he came to the San Francisco Ballet. I’m very proud to have him as a mentor.

Mettler: Last question: What’s the future of music delivery, as you see it?

Copeland: The music will be an implant, inside your brain. They’ll just inject it in one ear with a syringe, and presto!

Tags: Andy Summers, Ben-Hur, Blu-ray, CD, Circa Zero, DVD, film, Fred Niblo, Jeff Seitz, Les Claypool, LP, MGM, music, Peter Gabriel, Primus, Regatta de Blanc, Rumble Fish, So, Stewart Copeland, Sting, The Police, The Rhythmatist, vinyl, Virginia Arts Festival

Another great interview Mike. Well done !

[…] Mike Mettler is the former editor-in-chief of Sound & Vision, and he interviews artists and producers about their love of music and high-resolution audio on his own site, The SoundBard. An extended version of this story appears on www.soundbard.com. […]